As I wander toward finishing the new Amazon streaming series The Boys, adapted from the Garth Ennis comic book of the same name, I wonder about the state of American Superhero films as we approach year number twenty of the 21st century.

On the one hand, Hollywood has successfully corporatized, commercialized, and thoroughly commoditized the MCU through the Mouse House. This is in addition to the flopping around that Warner Bros. is doing with the Justice League and their crappy CW properties.

On the other hand, true comic book fans have a plethora of hero property options that range from the grim and gritty properties of The Watchmen and The Boys all the way to the adapted properties of The Crow, The Mask and other also-ran one-shots from the 1990s that are soon to be resurrected from the groove yard of forgotten hits.

With that range of choices, the clear winner — at least in the minds of the average film-goer — are the offerings from the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

What we have just watched being pulled off, in the last 15 years or so, has revealed a feast of riches the average comic book fan would never have thought to behold in our lifetimes.

Superhero film fans between the ages of 15 and 25, these days, have no idea of the miasma of comic book/comic film crap (remember the original Captain America film?) that came before them because they have basted in the glory of MCU film properties, treated with relative respect for the last 15 years.

Which brings us to the core problem of the entire superhero genre in general and how the genre’s core ideas can be further subverted, or even just maintained, in a world of social media, meandering attention spans, a growing Southeast Asian/East Asian film market with disposable income and a desire for fantasy, and, at a much larger scale, the declining American film culture overall.

Superhero Stories And Mythology

Superhero stories and mythology have always been compared to older mythologies of Western Civilization’s Greek and Roman gods.

The modern updating of those Gods’ stories in occurred mostly through the anthropological and writing and research of Joseph Campbell and others in the 70s and 80s.

On film, the fleshing out and relating of these stories for modern film audiences occurred through the work of George Lucas (Star Wars: OT), Steven Spielberg (Indiana Jones Trilogy) and others in films and through the works of Alan Moore (Watchmen) and Frank Miller (The Dark Knight Returns) in comics.

During that time the World — still in the grip of the Cold War — needed heroic, Western mythologies to balance out the extremes represented by the battle between capitalism and communism.

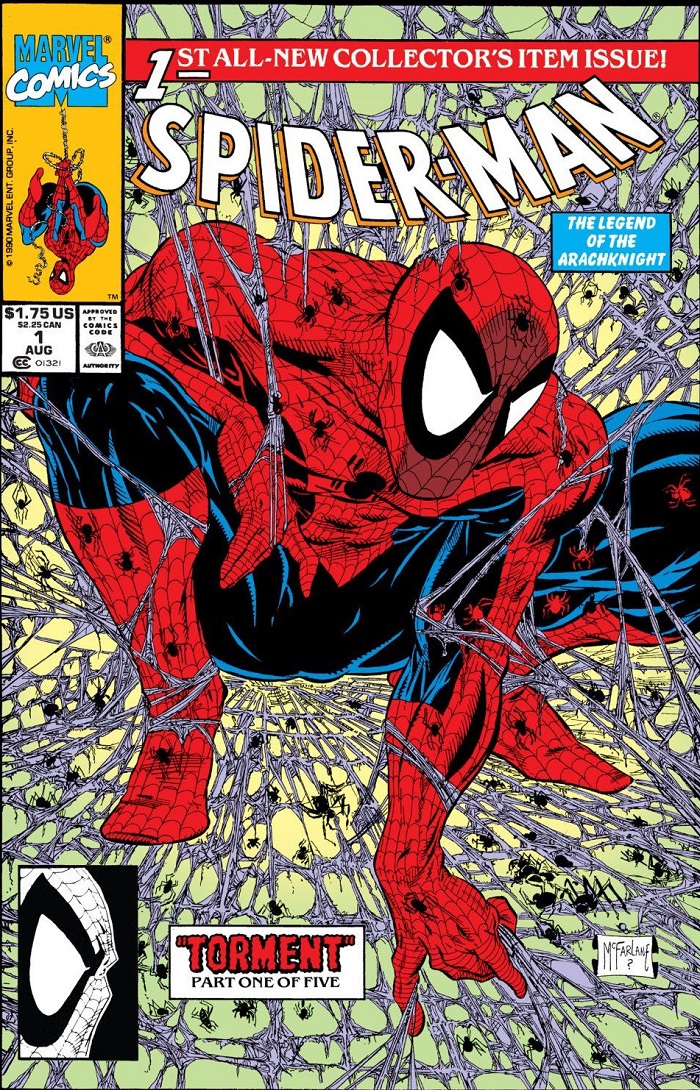

However, with the end of Communism and the rise of a “peace dividend” in the West through the 1990s, mainstream Marvel and DC superheroes languished in convoluted comic book storylines, pointless “reimaginings” and illogical multiple cover schemes.

The rise of Image Comics and other independent publishers and imprints aside, the imagination of the overall popular culture was not yet taken in with the large screen mythologizing of superheroics.

Yes, there were a few bright lights of the promise of the future transition from page to film (i.e. Batman, Blade, Men In Black, The Crow, etc.) but for the most part, the average, mythologically starved, the audience wasn’t there for tights on the screen.

Following the tragedy of 9/11, the release of films like the original Spider-Man trilogy, Hellboy, Hancock, the X-Men, and even Incredible Hulk over the next decade, began to meet the appetite for super-heroics that weren’t just grim and gritty, but were also grounded in “real-life.” This idea, previously really only explored in comics in Watchmen and The Dark Knight Returns, became the coin of the mythological realm for many casual audiences.

And then, Batman Begins and The Dark Knight really blew the doors off what Hollywood could do with balancing “real-life” political/social allegories while also addressing the increasing post-9/11 corporatization and commoditization of audience vision and appetites in an increasingly global marketplace.

The Future Of Superhero Myths

But what does all of this say about the future of superhero mythology on the small screen and the big screen?

When everyone (or, at least, everyone with a Twitter account) can be a celebrity to even a few people, what does being heroic (and possessing “God-like” power to back it up) really mean?

And, particularly in an American context, currently considered by many countries and peoples to be an unbeatable global behemoth in exporting cultural and entertainment messages to the masses about heroics, while also being exposed as having feet of clay?

The Boys successfully fleshes out these contrarian, non-mythological themes on the streaming screen. The story feels bigger because the principle idea of Watchmen, heroes that behave like “normal” people — with all of our foibles and problems — in a “normal” world, has now been brought to earth.

Principally to appeal to audiences whose attention spans are as limited as the vision in their Instagram Stories.

In reality, the story of The Boys feels appropriately small. And if Marvel Phase 5 is to be believed, the MCU is about to shrink as well. With this in mind, Marvel pulling their properties away from Netflix was a power move to consolidate a vision of mythological myth-making that will be smaller, more intimate, and, ultimately less in impact with global audiences.

Future attempts at large scale mythologizing will fail as the MCU wanders further into the confusing web of character development that the 70’s, 80’s and 90’s comic book development gave comic book fans.

Which means, more true fans are about to have their hearts broken by Marvel and Disney, but on the small screen, comic books fans should take heart: There will be more properties like The Boys made in the future for small audiences and fewer properties that will attract the true fan.

The future of comic book heroes on the small screen is bright.

As the large screen audience who want heroic mythology at a global level continues to fragment, and as more and more properties at the MCU scale will be forced—through bean-counting considerations—to film mythologies that will appeal to a watered-down audience, on the small screen, TV will continue to be the place where smaller properties that reflect the real maturation of belief in heroism of any kind can survive.

As the need for heroes behaving super-heroically continues to grow — it turns out we do need a hero — the commensurate cynicism and disbelief will grow as well.

And, when the inevitable decline of superheroes does arrive, probably around the end of this century, its glorious run — both large and small scale — will be remembered with the same fondness that fans of Old Westerns remember that genre today.