A Man Named Sandy

Sandy Peterson first discovered the works of early 20th century horror author H.P. Lovecraft in a World War 2 Armed Services Edition of The Dunwich Horror that was gathering dust in his father’s library. These small, cheap paperbacks were distributed to servicemen during the war.

One can only imagine the logic behind distributing tales of New England hillbillies interbreeding with rapacious tentacle aliens in the woods to men already experiencing horrors on the battlefields, but there ya go.

Peterson quickly developed an obsession for Lovecraft, and as a student at the University of Berkeley in the 70s, where he interestingly enough majored in Zoology, he developed another love — Dungeons & Dragons. Like many D&Ders, he often conceived of working Lovecraft’s nasty mythos into his games, but also had an idea for a game truer to Lovecraft’s 1920s settings.

We’re Trying To Make A Horror Game Here

Around that same time Oakland, California game company Chaosium, makers of popular D&D alternative RuneQuest, were themselves trying to get a horror game together. One concept had modern times as a setting for Lovecraftian horror, but other ideas included D&D style fantasy but with more Lovecraft themes. They were having some trouble, not the least of which was successfully getting license from copyright holder Arkham House, who did not like the offered manuscripts or ideas.

Around that same time Oakland, California game company Chaosium, makers of popular D&D alternative RuneQuest, were themselves trying to get a horror game together. One concept had modern times as a setting for Lovecraftian horror, but other ideas included D&D style fantasy but with more Lovecraft themes. They were having some trouble, not the least of which was successfully getting license from copyright holder Arkham House, who did not like the offered manuscripts or ideas.

Along came Sandy Peterson, who was more and more becoming convinced that playing Lovecraftian characters against sanity-draining horrors was a viable notion. Chaosium head Greg Stafford was impressed with Peterson’s vision, and Sandy got the job of making the game a reality.

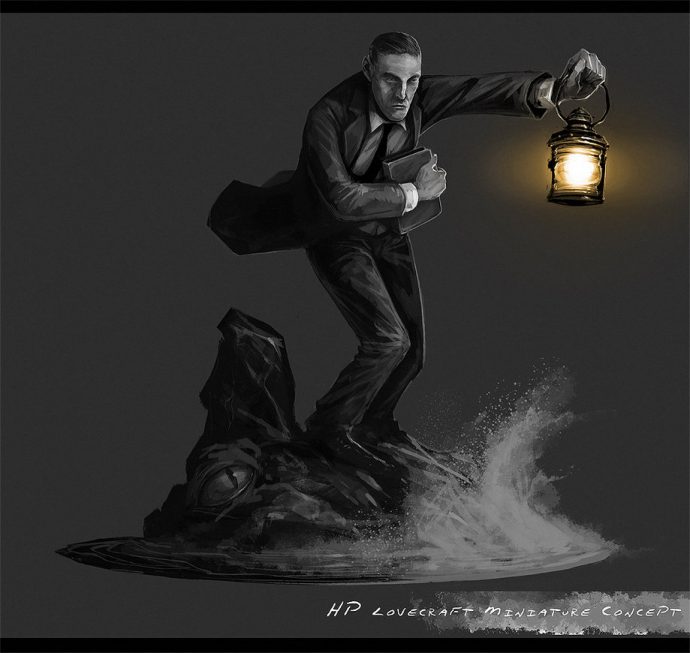

Call of Cthulhu would see players take on the roles of Lovecraftian heroes: journalists, artists, students, professors, etc. It seemed a strange notion; Lovecraft’s protagonists tended to be much like him, milquetoast xenophobes who tended to faint dead away at the sound of a mouse fart. But Sandy was committed to the vision.

The first edition of the game, released in 1980, was an immediate success.

Play The Game

Unlike games such as D&D, where you start your character as a fearful poltroon and eventually try to level him up to a great heroic warrior by delving into dungeons and taking monsters head-on, Cthulhu had no such quest. Basically, you tried your best merely to survive and to try desperately to maintain your sanity as it was slowly drained away and you invariably developed various neurosis.

In a standard CoC game, characters would more slowly investigate various nefarious doings, and peel away layers of the story like an onion, until eventually facing the prime force behind the evil nature of the session.

That final foe may be a cultist sacrificing victims in an old warehouse, an animated skeleton rattling around in the basement of an old house, or if they were very unfortunate, some cosmic horror lurking in the woods that could do anything from eating you, stealing your brain to take back to it’s home dimension, or just blasting your sanity and sending you gibbering off to the local asylum to eat flies and bang your head on the walls till the end of your days.

It was an option for more assholish Keepers to grab up your character sheet and rip it to shreds while cackling.

Guns Against Cthulhu

Many fans of the game, Keeper and Investigator (the players) alike, were purists and most enjoyed the no-win scenarios of one-shot sessions. But seeing as the game was based off of Chaosium’s Basic Role Playing game engine, there was some room for character improvement of skills. BRP was based almost entirely on percentiles. No leveling.

You might, for example, have a 25% chance to hit with a handgun, and if the character as successful with the roll there was a chance to improve by 5%. It was a simple and elegant system, but hardly necessary if you were going to be rolling a new character in a game or two.

Thus there came a quick evolution of Keepers such as yours truly, who more enjoyed ongoing campaigns. In games such as this, often called “Guns against Cthulhu”, you could come up with characters much more capable than the wimps of typical Lovecraft tales.

Pulp adventure characters were certainly on the table in my games. So my campaigns included the likes of big game hunters, mercenaries, mobsters, Chinese cooks with martial arts training, Indiana Jones types, boxing champs, even an Anastasia European lost-princess type.

These games were more in line with stories written by later authors who spun Lovecraftian tales where heroes could often take it to the grill of the once invincible monsters of the original mythos.

With characters like these, and the judicious use of more combatable foes such as cult henchmen, assassins, thugs, etc, plus lesser monsters such as the aforementioned skeleton, zombies, ghouls, and the like, characters had a chance and could last multiple sessions.

My Greatest Campaign

Even with these more powerful and resilient heroes, happy endings were rare in the game. In my last big campaign years ago, the deposed princess and the party made it to her fictional kingdom to face her murderous usurper uncle.

In the final fight as she struggled with her foe, another heroic but foolhardy character fired his elephant gun at the uncle, rolled a “00” on his dice (a “catastrophic failure” in the rules), and blew the head off the princess.

It was a bummer for those two players, but I could not have come up with a more terrible ending. Some characters actually escaped back to America, so it was not a total party kill like an encounter with Cthulhu himself would be. I consider it my greatest campaign, and over many genres I’ve run a lot of them.

Choose Your Era

For Keepers who want to explore time periods other than HPL’s 1920s, there are supplements to assist. You can run games in the 23rd century (Cthulhu Rising), modern times (Cthulhu Now), The Victorian era (Cthulhu By Gaslight and Horror On The Orient Express), The Dark Ages (Cthulhu: Dark Ages) and even ancient Rome (Cthulhu Invictus).

Expansion

Call Of Cthulhu has had several editions over the years, and has had video game and card game spin-offs. Mythos was a CoC card game in the 90s that I loved (I still own a complete collection), but it was released at a time there was a glut of collectible card games, and it ended up being a loss for Chaosium.

After all these years, Call of Cthulhu remains popular. But it’s the game’s original popularity that still amazes. Now Cthulhu references are everywhere, and you can buy everything from T-shirts to plushies of the Great Old One. But in 1980, Lovecraft was still fairly obscure. The game never had the popularity of D&D, but it deserves props for making horror a viable gaming option over elves and hobbits.