Greetings, programs! Your personal gaming historian Captain Jerk here with another trip to the distant past. Today we will take a look at the first three early attempts to capture that fantasy game magic that D&D had cornered the market on in the early days of roleplaying games.

The local gaming store was a weekend hangout for me as a kid; I witnessed these early releases and owned all of them. They have varying degrees of popularity, but I present them here in order of publication.

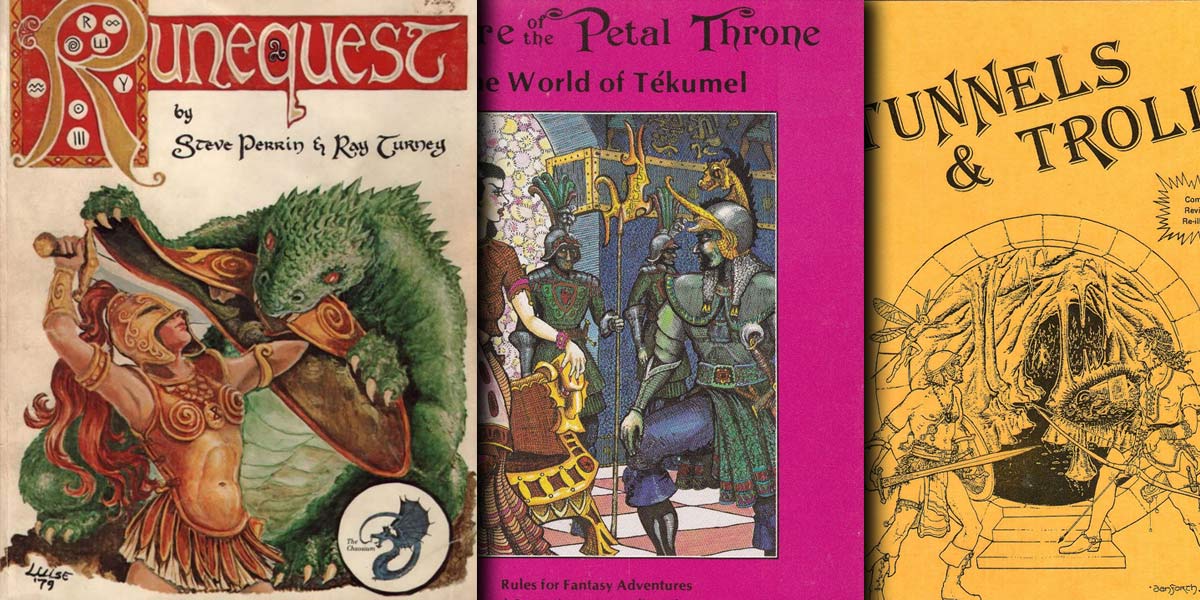

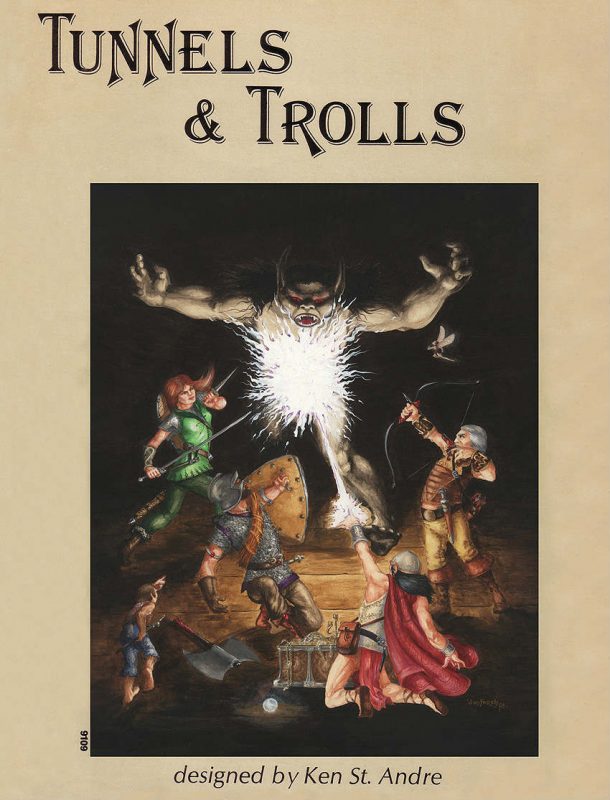

Tunnels And Trolls

In 1975, Ken St. Andre, a Phoenix Arizona librarian, was relaxing and having a read of the rules for the new role-playing game Dungeons and Dragons, and felt a headache swiftly coming on.

He was intrigued by the prospect of playing out fantasy scenarios, but the vague rules (aimed at those few already familiar with Gary Gygax’s wargame Chainmail) were bewildering to him, as they were for many others at the time.

So Ken set out to create a more approachable set of rules for easier play, and Tunnels and Trolls was born.

The game, though seen by many as a blatant rip-of of D&D, was almost immediately popular. Not only was it much easier to learn and play than D&D, but it focused more on a sense of whimsy over its more serious predecessor. Many spells, with names such as “Take that You, Fiend!” imbued the game with a certain silliness. Still, the game featured many of the same things that made D&D appealing.

Physical statistics and character classes aped D&D to a certain degree, and of course it’s combat “crunch” relied on rolling weapon dice against physical damage points. But instead of an array of multi-sided dice, normal six-siders were the only needed. And you needed a lot. Both sides of a conflict rolled a dice total into a communal pool, and the side with the highest number “won” that round, with the other side dividing up the damage among them.

T&T’s publisher, Flying Buffalo, released many solo gaming modules that worked out much like Adventure Path books but with actual combat resolutions.

Favorites of mine included Mirror World and Naked Doom.

In Mirror World, you step through the magical mirror of Marcekanius the Fair, dwarfish merchant of Tallymark and find yourself in a series of strange adventures. Adventures where a one-eyed statue demands the return of his other eye, a bizarre and misshapen creature grunts its name, but says nothing more (Groot?) and a towering fiery monolith offers great power — or even greater doom!

Naked Doom finds you arrested by the town guard of Khazan, a city-state which does not believe in coddling criminals. Now you must run the Royal Khazan Gauntlet of Criminal Retribution and Rehabilitation. You are taken into the catacombs, beneath the Khazan Courthouse, and stripped of all clothing, jewelry, weapons, amulets, and other devices. If you can make your way through the series of tunnels and caves that lie ahead, you will escape with your life — and if you’re lucky, treasure!

Tunnels and Trolls maintains a large fanbase to this day. Ken St. Andre, a rascally and spry (for his age) character, still remains a convention staple, hyping his game and throwing verbal shade on D&D at every opportunity. He also does this:

Empire of The Petal Throne

M.A.R. Barker was a linguist and University professor who created the fictional world of Tekumel decades before it’s official 1975 release. Mostly as a setting for creating alien languages, but he also ultimately may have had novels in mind, so obvious comparisons can be drawn to the works of JRR Tolkien. But first and foremost, he just enjoyed creating a unique setting with weird races.

Barker was introduced to D&D not long after it’s release, and it immediately dawned on him that Tekumel would make a good game setting.

Tekumel was a world that had been colonized by space faring humans. The colony somehow fell into a dimensional vortex and merged into a planet of warring alien empires. (Or something) It’s a fairly complicated setting.

EOTPT has a system that is clearly inspired by D&D, with physical and mental statistics for characters. But it’s the setting that set itself apart from typical European styles found in most fantasy RPG games. Tekumel was heavily inspired by South American ancient civilizations, though also leaning somewhat to more familiar settings with a sword & planet feel, such as the civilizations of John Carter of Mars.

In the original rules character motivation was rather narrow. All new player characters arrived by boat to an unfamiliar port in the Petal Throne Empire. Penniless fighters, sorcerers, or priests looking for work. That work usually involved dungeon crawling.

Yup, dungeon adventures are without a doubt taken from D&D. But delving into them by characters in EOTPT tended to have other goals than the usual murder hobo scenarios. Sure, gold and magic swords are to be found, but in Tekumel you might be going into labyrinths as a right of passage, to engage in faction warfare, spiritual vision quests, or as spectacle for nobility.

A certain lack of promotion, and a complex, non-intuitive setting were among reasons the game never became more popular. But to this day there remains a small but devoted following among aging neckbeards, and there are even fanzines still being produced.

Runequest

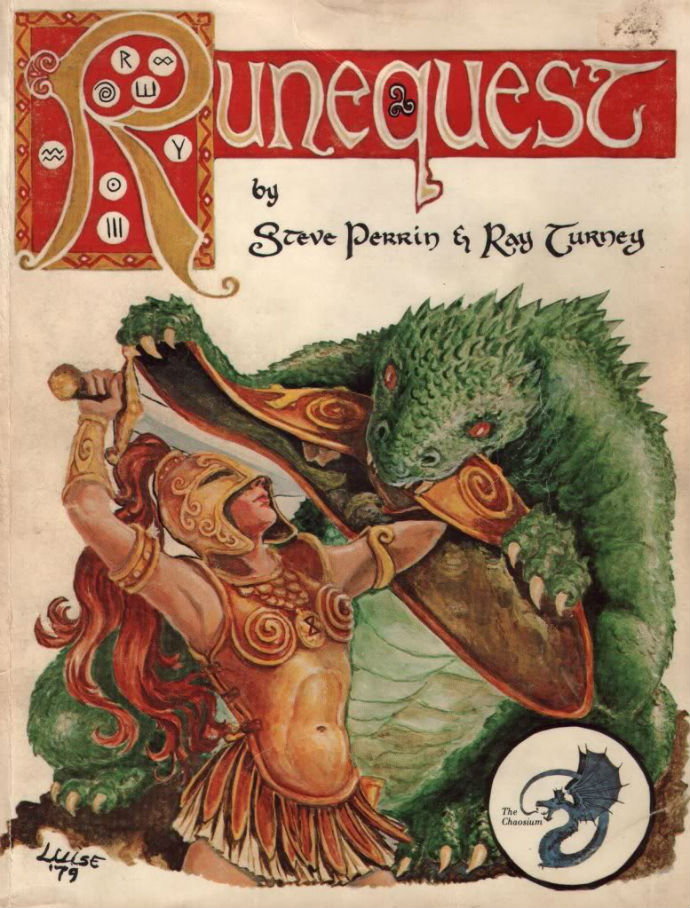

In 1975, Greg Stafford produced the board game White Bear, Red Moon, based on his own complex fantasy setting Glorantha. Greg founded Oakland California game company Chaosium to market the game.

An avid D&D enthusiast, Stafford created the Basic Role Playing system as a D&D rules alternative, and ran his games in the Glorantha setting from his board game. In 1978 Chaosium produced it as their first major role-playing fantasy game, Runequest.

Using the Basic Role Play system Steve Perrin developed, characters in the game advanced by increasing skills, eschewing D&D’s level advancement. With luck, a low-level character could get a lucky hit and kill or cripple a more advanced player character. No astronomical hit point totals.

And due to the systems hit location focus, losing a body part was a real danger. It came off as far more realistic than D&D’s abstract combat, and this was one of the main strengths of the game.

Glorantha itself was a fabulous setting, filled with complexity and variety. Campaigns could start in any number of locales with characters being from areas with thunder-worshipping celtic-style barbarians, arid plains with beast herders (who herded and rode any kind of herd animals BUT horses, which were taboo. So zebra, buffalo, antelope, or even rhino riders were common), or greek-style imperials of The Lunar Empire who worshipped the moon.

Glorantha was just moving past a Bronze Age, so in keeping with that fact most characters began with weapons and armor of weaker materials. Weapons tended to break in combat. Characters, instead of coveting magical swords, sought out rare and expensive iron equipment.

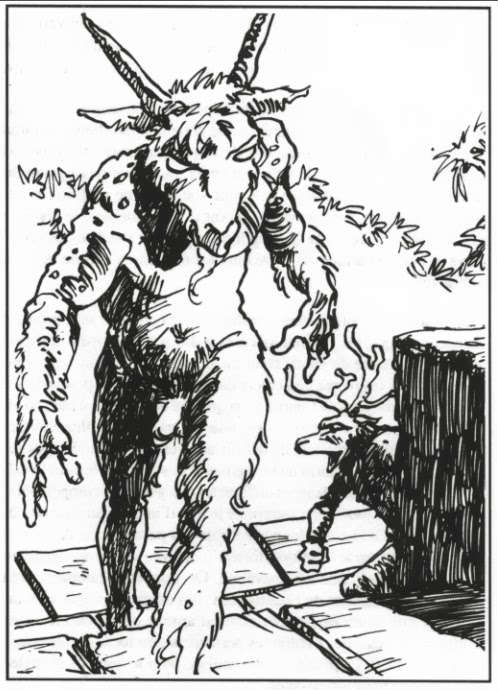

Glorantha featured a very gritty adult setting. Instead of orcs, fearsome humanoids included Broo, or Goatkin; rape-goddess worshipping, diseased beastmen who were all male and reproduced through kidnap and rape of human females. Yikes.

In all areas of Glorantha, worshiping gods was a main aspect of life. It is very difficult for characters to reach full potential and an End Game without belonging to some cult or another.

An interesting thing about RQ characters is all characters had the potential to use Rune Magic spells, eliminating clerical archetypes. All characters were potentially clerics and sorcerers on top of being fighters.

A typical Glorantha campaign will start in a small village with characters as human teenagers starting out on their quest for skill improvement, but a wide range of races can be run by players. Trolls, Minotaurs, Centaurs and other oddities can be chosen if the game master allows, and, of course, elves and dwarves are around (sorry, no hobbits).

One of the more interesting character possibilities are Dragonnewts, humanoid lizard men who start out the size of dwarves. They are essentially immortal; resurrecting back at their home nest, and coming back in a bigger and stronger form if their skills have been developed to a certain degree.

Over the decades Runequest has remained D&D’s number one fantasy game alternative, and the game’s publishing has had a very storied history. Some releases even went with other settings other than Glorantha. It’s system was adapted for other releases based on the Elric stories and King Arthur, and most famously for Call of Cthulhu.

But whatever edition that comes along, Runequest remains popular to this day.

Endless fantasy RPG’s have been produced by various companies over the years, including in recent years “Fantasy Heartbreakers” (fan produced games with small followings), but nothing has been able do much more than stand in the shadows of Dungeons and Dragons. D&D, as it always has, remains the 800 lb. gorilla in the game room.