INTRODUCTION

In April, 2015, Lucasfilm Limited, a company founded by filmmaker George Lucas and recently acquired by the Walt Disney Company, sponsored a massive convention called the Star Wars Celebration in Anaheim, California. This week long congregation of Star Wars fans featured as its keynote event an interview with the director of the upcoming Star Wars Episode VII: The Force Awakens, J.J. Abrams. During the interview, Anthony Brezlican from Entertainment Weekly said to Abrams, “one of the things that’s been noted about this film is – Star Wars has always pushed the boundaries of visual effects but you’re kind of taking a retro approach this time around. You built a lot of practical sets. I hear people like that.” The audience erupted in applause. Once the applause died down, Abrams responded, “that’s an awesome reaction… When we started talking about actually what the story would be and how to make it happen, the thing that struck me…. was just how real you knew Star Wars was and felt when you first saw A New Hope… We needed to set a standard that was real and you felt like you knew the people were in those places… You want it to be legitimate. You want it to be authentic.”

This conversation reveals the reverence many Star Wars fans have for the look and feel of the earliest films in the series, which used 1970s and 1980s technology to bring their outer space characters and worlds to life. This reverence is critical to understanding the subset of fans who engage with Star Wars films and television programs by taking this existing content and recutting it, repurposing it and sometimes even adding their own content. The term for this kind of cultural content appropriation and reconstruction is a ‘fan edit.’ While some fan editors use existing content to create homages to their favorite characters and situations (which often emulate the look and feel of music videos, created from mashups of clips from movies and TV shows mixed with existing music), others use the audiovisual tools at their disposal to ‘fix’ the problems they see in the films and shows that simultaneously fascinate and irk them. It is difficult to get a sense of who these fans are, in terms of demographics, because of the illegality – real or perceived – of re-editing films and television shows and distributing them via the Internet.

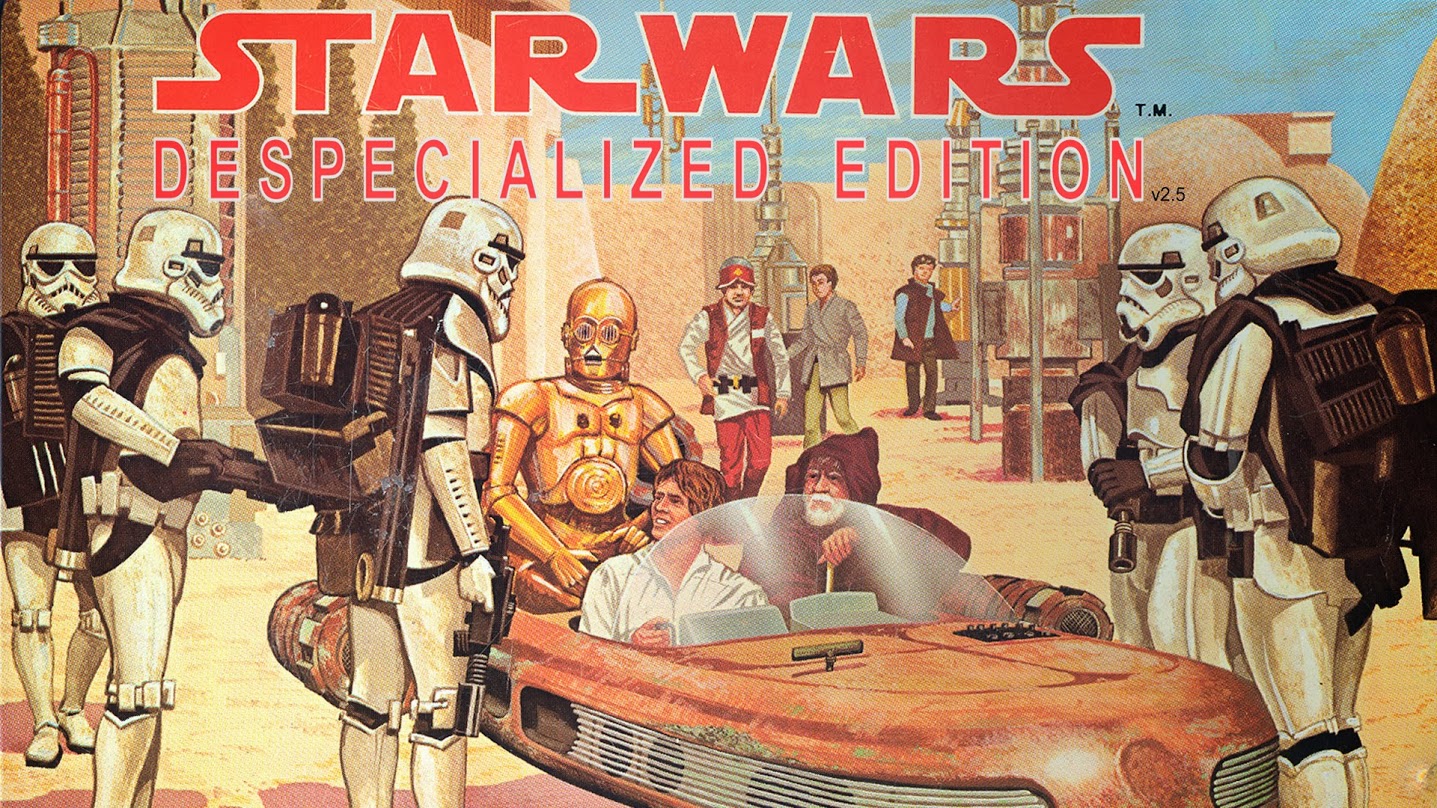

One ‘problem’ that many fan editors seek to fix relates to the ever-changing vision that the creator of the Star Wars mythology, George Lucas, has had for the first three films of the series. Lucas created these films, referred to as the ‘Original Trilogy’ or ‘OT’ by many fans, in the mid-1970s to the early 1980s using, of course, the practical special effects technologies of the time. The limitations of the miniature and man-in-suit effects troubled Lucas and, in the mid-1990s he released the ‘Special Editions’ of the trilogy in order to upgrade these special effects and drum up interest for his upcoming, self-financed Star Wars prequel films. Lucas, in attempting to fix these issues in the classic films, integrated state-of-the-art computer generated imagery (CGI) into existing footage in order to update it. In so doing, Lucas created new iterations of these films that hewed more closely to his original vision for them – a vision that he claimed was constrained by the effects technologies of the 1970s and 80s. These actions, coupled with Lucas’ refusal to release high-quality home video versions of the unaltered Original Trilogy, inadvertently kicked off the creation of Star Wars Despecialized – an attempt by a distributed network of fan editors to create and disseminate high-quality iterations of the original Star Wars trilogy against the express wishes of these films’ creator. The view, shared by many of the contributors to this Despecialized project, that Lucas’ Star Wars Special Editions are inauthentic versions of these stories, is at the heart of this community of practice. In the case of Despecialized, this shared commitment is to generating ‘authentic’ versions of these films so as to allow this community to see the Star Wars trilogy in what is, to them, its most authentic iteration: the original, unaltered theatrical releases.

HARMY, STAR WARS DESPECIALIZED AND THE WORLD OF FAN EDITS

Star Wars Despecialized is largely – but not exclusively – the work of one person, Petr Harmáček, an English teacher in Czechoslovakia, who goes by the name of ‘Harmy’ online and refers to himself as a ‘Guerilla Restorationist’ on his OriginalTrilogy.com profile description. (OriginalTrilogy.com is a website developed by and for fans of the unaltered, original releases of the Star Wars trilogy.) Harmy advertises his Despecialized editions of the films on the site’s user forum. Harmy also uses YouTube to upload videos that describe, in very technical detail, how he created Despecialized. On this YouTube page he describes the Despecialized project thus: “‘Star Wars: Despecialized Edition’ is a fan edit project with the goal to reconstruct the original theatrical releases of the Star Wars original trilogy (Episodes IV, V, & VI) at a quality comparable to the high-definition medium of our time.”

It is worth noting that Harmy bears little ill will towards Lucas’ Special Editions. Harmy does not see his Despecialized project as a way to supplant Lucas’ altered versions of these films. Rather, he sees his work as a (guerilla) restoration project to recreate the original iterations of the films so that they can rest comfortably, side by side, with the special editions. Many Star Wars fans are ambivalent to the Special Editions but look upon the lack of an official release of the Star Wars films in the form they remember growing with as an insult to fandom.

However, Star Wars Despecialized is not solely the work of Harmy. As will be discussed in more detail below, the Despecialized editions relied on a network of Star Wars fans, with the OriginalTrilogy.com message board as their locus, to donate shots and scenes from various home video (and film) iterations of the movies to the effort. Harmy combined these snippets of content to create the Despecialized editions and while he was doing this for posterity, other fans saw this work as a way to right the wrongs – as they saw them – in Lucas’ adulterated versions.

One such wrong has been an ongoing aggravation for fans: the ‘Han shot first’ fan controversy. In the original version of Star Wars, roguish hero Han Solo is confronted by an old nemesis, the bounty hunter Greedo, who pulls a weapon on him. The narrative flow of the scene makes it abundantly clear that Solo’s life is at risk, so our hero shoots Greedo under the table before Greedo can shoot him. In the 1997 Special Edition, Lucas adds a computer-generated laser bolt from Greedo’s weapon before Solo’s shot, in order to make Solo’s action more explicitly self-defensive. Many fans were angered by this edit because they thought it diminished the ‘scoundrel’ nature of their hero. This tension between Lucas’ view of the character and the fans’ is, at base, a question of who the ‘authentic’ Han Solo is. For the fans, many of whom had had two decades of access to the original cut of Star Wars in theaters and/or on home video, Han Solo shooting Greedo under the table established Solo as an anti-hero, a darker character to contrast against the unimpeachably honorable Luke Skywalker. Lucas’ Special Edition of Star Wars shows us the director’s vision of the character and this vision – of a man who is acting out of self-defense – fails to show us this dark side. This scene, restored in its original version in Star Wars Despecialized, is very important to fans.

While Harmy is using Despecialized to preserve and restore the earliest theatrical versions of the original trilogy, he and the other contributors to the project are also working to restore their shared vision of the authenticity of a character who is so crucial to the Star Wars saga. This ‘righting of wrongs’ is an important part of the realm of fan edits. Lucas claims to have a monopoly over the authenticity of the character of Han Solo because he is the character’s creator. The Despecialized community, however, challenges this monopoly on the grounds that they have spent decades with this original depiction of the character – a depiction that, to their minds, conflicts with Lucas’ later reinterpretation.

THE FANS VERSUS GEORGE LUCAS

The ‘Han shot first’ controversy shows the conflicting feelings that Star Wars fans have for the films’ creator. Star Wars fans often freely admit their debt of gratitude to ‘George’ for creating the Star Wars universe but, at the same time, they often feel betrayed by him for making changes to this sacred space. These changes can be dramaturgical – like Greedo shooting first – or they can be stylistic like the inclusion of CGI in the original trilogy and the overwhelming preponderance of it in the prequel trilogy. (This distaste for CGI, loudly expressed by many Star Wars fans such as those present at the 2015 Star Wars Celebration described above, has motivated Disney/Lucasfilm to loudly and proudly promote the ‘old-school’ filmmaking techniques – practical sets, model-building and people-in-suits – employed in the production of the upcoming Star Wars Episode VII.)

This reverence/frustration for Lucas and the Star Wars films plays out visibly in the world of fan edits beyond Despecialized. One infamous fan edit, known as The Phantom Edit, circulated as a bootleg in the early 2000s and can still be found online. The creator of this edit of Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace went to great lengths to erase all traces of the CGI character Jar Jar Binks from this version. The Jar Jar character has become a symbol for many Star Wars fans of an unwelcome, ‘kiddie’ element in what they see as a serious filmic saga. The ‘Phantom Editor’ attempts to ‘save’ the critically-maligned Phantom Menace by deleting the character and tightening up the narrative by trimming up long, expository dialogue scenes. This is one of the central tensions of fan edits: because fan editors do not usually have access to the original actors, outtakes or sets for the original films, they must work with what they have, which is usually the ‘flawed’ professionally-released iterations with which they take issue. In other words, there is only so much of a narrative that a fan editor can fix.

While fans may seek to ameliorate these films by editing out or changing those things that frustrate them, they rarely, change the major themes or ‘beats’ of the films. Fans, in searching for a more authentic-to-them experience of Star Wars, tend to concede the need for their edits to hold to the larger arc of the film or television show they use for fodder. So while they are operating to express their vision of the authenticity-in-the-micro that lives in diegetic elements like characters and situations (Han shooting first, removing Jar Jar), they still hew to the larger narrative vision of the original creator(s) of the content which is, to the fans, authenticity-in-the-macro. The story of Star Wars fan edits, Phantom Edit and Despecialized included, is often the story of fans working to ‘save’ a beloved franchise from its creator.

Despecialized Why and How

The Phantom Edit is an attempt by one person to ‘improve’ a film’s dramaturgy so as to recapture a more mature vision of the Star Wars universe. Despecialized is an attempt by a group of people to restore the original versions of the classic trilogy of films. This group of fans were disgruntled at the lack of an official Blu-ray release of the original, unaltered trilogy (called the ‘GOUT’ by Harmy – George’s Original Unaltered Trilogy).

Harmy works with bits and pieces of footage from the Star Wars trilogy cadged from various home video and film elements in order to do what Lucas would not. Unlike the Phantom Edit, Despecialized does not make substantive changes to the narrative elements of the films (although some fans may argue the point where Han Solo and Greedo are concerned). Because no one home video release of the ‘GOUT’ was free of the running changes Lucas integrated into his films over the years – even before the Special Editions – Harmy put out a call on the OriginalTrilogy.com website to other forum participants for specific elements from their Star Wars videos to integrate into one widescreen, high-quality iteration. Harmy has produced a brief video, distributed via YouTube, to explicate his processes for color correction, subtitling and digitizing the analog elements needed for Despecialized. OriginalTrilogy.com users posted a list of the elements Harmy used for the Despecialized version of the first film, complete with the user names of some of the contributors.

To make Despecialized, Harmy used many video and film sources to decouple the original trilogy from the CGI imposed upon it by its creator. In some cases, this undoing reveals performances and footage that were literally occluded by 1990s-era special effects.

In removing the CGI elements from the Star Wars films, the contributors to the Despecialized effort are trying to preserve their vision of the “true” trilogy. Their community of practice is not just bound up in the work they are doing. It is also, for many of them, bound up in their nostalgia – their memories of having seen the original, unaltered trilogy of films in their first theatrical runs. In the case of Star Wars Despecialized, the sense of community that binds the contributors to the project – and the consumers of the ultimate products – is largely predicated on having been a theatergoer in the 1970s and 1980s.

Star Wars fans have used the Internet to communicate and share gripes about their favorite films since before there was a World Wide Web. However, in recent years the costs of video digitization, production and post-production have lowered dramatically. Very sophisticated video transcoding and editing software can be found for free on the Internet. The increase in access to these tools, along with dissemination tools like YouTube and BitTorrent (more on them later) and communications technologies like Web forums, has fueled the fan edit community and allowed Harmy and his collaborators to create Despecialized. As Joshua Wille notes, “Lucas pioneered digital media revisionism, and this technology was inherited by his audience.

Traditional film editing equipment remains inaccessible to most people, yet basic nonlinear video editing software is now standard on most computer operating systems. The cost of remixing and repurposing video has come down enough that it now parallels the remix/reuse music culture, which is a decade or so older. Video, like music and still images before it, has become manipulable by the masses. This ease of production and distribution has helped the Despecialized films have a global reach and impact. It has also helped to strengthen a Star-Wars-related sharing economy that has fewer barriers to access than ever before.

HOME VIDEO, COLLECTING AND PIRACY

Fan edits are not the first example of the collecting and trading of home video in general and Star Wars in particular. Nor are fan films strictly a twenty-first century phenomenon.

A 1978 fan film called Hardware Wars, which lampooned Star Wars by using kitchen appliances to stand in for the original film’s spaceships, did quite well in short film festivals and became George Lucas’ favorite parody of his own films.

Bootlegs of Star Wars products have not been restricted to fan edits, spoofs or cinematic content. The infamous “Star Wars Holiday Special,” a made-for-television event that has aired only once, in late 1978, has circulated for years on home video. This special, deemed so awful by critics and general audiences, has been disavowed by Lucas and has never seen an official, Lucasfilm-sanctioned release on home video. Any copy downloaded, traded or viewed on online is thus an illicit, bootleg copy. In a 2007 screening of a clip from the Library of Congress’ digitized copy of the “Holiday Special” for the Association of Moving Image Archivists annual conference, the following description can be found in the screening’s program: “After considerable curatorial deliberation, the Library of Congress presents (on tape) a clip from the first 3⁄4″ U-Matic digitized at the recently opened Packard Campus in Culpeper, Virginia. We hope the next 249,999 U-Matics will prove as scintillating. The clip is offensive only to those who worship the original work from which it derives.” No mention is made in the program of the name of the clip and when the first frames of the special appeared on the theater screen, an audible groan followed by laughter came from the assembled viewers.

Theatrical prints of the original films were usually owned by 20th Century Fox so they rarely found their way into the hands of private collectors. Some did, however, and this has proved to be a boon to Harmy’s work on Despecialized because it helped him determine, for example, where the subtitles for Greedo’s outer-space-dialect should register on the screen. Harmy notes (correctly) that collectors who hold bootleg copies of films have occasionally proved helpful to restoration or preservation efforts. Harmy’s view of his own work is not that he is improving the original trilogy but, instead, preserving it for future generations.

BITTORRENT, YOUTUBE AND ONLINE DISSEMINATION

For decades, fans traded the “Star Wars Holiday Special” on videotape. 20th Century Fox released the widescreen version of the unaltered original trilogy on the laserdisc format in 1993 with remixed digital audio sound. (The laserdisc format is analog video with digital audio.) This was, until 2004’s DVD release of the unaltered trilogy on DVD, the only way to procure letterboxed copies of the original trilogy without the Special Edition edits. For many years fans circulated laserdisc-to-DVD bootlegs of the unaltered Star Wars trilogy. Harmy notes that while these bootlegs copies were often of relatively high quality, they were not adequate for preserving the look and feel of the original films. Furthermore, many fans felt betrayed by Lucasfilm’s decision to use these laserdisc copies as the masters for their official release of the film, rather than returning to high-quality digital or film masters. This betrayal is part of what encouraged the Despecialized community to take on the mantle of creating high-quality iterations of the unaltered trilogy themselves.

The Phantom Edit circulated on on tapes between close friends of its creator but copies quickly began to spread like topsy. What started as a lark and a fan edit to exchange with friends quickly evolved via the Internet into a minor media sensation.

Like other contemporary fan edits, Star Wars Despecialized uses BitTorrent as its primary distribution mechanism. YouTube has proved to be a poor method of distribution for Despecialized because the site employs complex software to prohibit copyright-infringing uploads. Information about how to obtain the Torrent files needed to initiate a download via BitTorrent is disseminated in speakeasy fashion. You have to know where to look, and Harmy makes this explicit on his YouTube page. Using BitTorrent to distribute the Despecialized edits is rather like using Napster to distribute music in the last years of the twentieth century. The production of Despecialized goes against George Lucas’ stated vision for his films. Dissemination of Despecialized goes against the economic interest of Lucasfilm.

This dissemination of fan edits is not always passively accepted by the creators of the original content. BitTorrent, a common distribution mechanism for fan edits, has been seen as a threat to Hollywood’s bottom line for years. Video fan edits were, up until 2008, cataloged on a website called Fanedit.org. The website contained direct download links to video files as well as Torrent files that would allow the user to download video files via BitTorrent software. In 2008 the site was forced to concede to a copyright infringement claim made by the Motion Picture Association of America under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act and take down these direct download links and Torrent files.

Despite Harmy’s directive to ‘not support piracy’ on his YouTube video pages, the use of BitTorrent to distribute fan edits like Star Wars Despecialized is a very direct and specific challenge to the traditional, top-down (theatrical and home video) distribution channels for the original works. In this way the battles between Napster users and the American music recording and publishing industry of over a decade ago have mapped onto the current attacks on fan edits. It is clear that the fan edit community, like the turn-of-the-century music file sharing communities, represents a conflict of interest between producers and users of content.

LUCAS AND STAR WARS

George Lucas spent decades at the helm of the Star Wars franchise and his often contradictory attitudes toward filmmaking and film preservation make him a vexing figure for Star Wars fans. Fans respect Lucas for creating the world in which they play but the nature of that play often indicates a lack of respect for many of Lucas’ creative decisions. One of those decisions is the aforementioned Special Editions, which made significant changes to the established film trilogy. Lucas, plagued by the limitations in effects technology he employed in the original trilogy, spent several years considering how to update the effects in these films. In Lucas’ mind, these changes were necessary to conform the existing, ‘flawed’ films to his vision. Lucas has emphatically asserted that the Special Editions are the true manifestation of his creative vision. It is clear that Lucas views each of his films as a palimpsest, a work to continually erase and rewrite up until the moment it is ‘ripped out of his hands.’ Is it that surprising that Star Wars fans would also view these works as ripe for their own refashioning? Even in subsequent home video releases of the Special Editions, Lucas has added scenes, updated (again and again) some effects shots and fiddled with edits here and there (Kirby, 2012). He has done this so much that he has, in fact, often been accused of playing the fan editor himself.

Another example of Lucas’ changes in the Special Editions is the digital insertion of the character Jabba The Hutt into the updated version of Star Wars. When he worked on the this film in the 1970s, Lucas intended to have Jabba confront Han Solo early in the film. Lucas, always intending for Jabba to be some kind of special effect (and who later would be a special effect – a huge animatronic puppet in Return of the Jedi), shot the scene with a human actor standing in for what would later be some kind of monster. For time and budgetary reasons, Lucas abandoned the scene and it was not included in the film’s 1977 release (although snippets of the scene, with the human stand-in, can be found in making-of specials and documentaries of the time). For the 1997 Special Edition, Lucas and his technicians at Industrial Light and Magic (ILM – the special effects house that was born from the first Star Wars films) used CGI to create a Jabba that matched (arguably) the animatronic from Return of the Jedi. For the release of the Blu-ray iterations of the Special Editions a decade later, Lucas and his team ‘revised’ Jabba to better conform to his Jedi grandeur (See Figure 4). Despite Lucas and ILM’s efforts, Harmy and his collaborators removed the scene entirely from Despecialized.

It is worth noting that fan reaction to the scene has been mixed. While some enjoy it for the opportunity it affords to show a mid-1970s Harrison Ford as Han Solo in what feels like a new scene, others find the CGI Jabba to be no match in verisimilitude to the practical effect of Return of the Jedi. Interestingly, Despecialized gets to completely elide this fan controversy be excising the scene altogether.

Harmy, like the other contributors to Despecialized, view many of these changes as a kind of vandalism and even accuses Lucas of wanting to destroy the original films. It is no wonder that woven into the raison d’être of the Despecialized films is this narrative of ‘saving these films from their own creator.’ The fact that even some of the key contributors to the early Star Wars productions are troubled by the changes Lucas wrought in the Special Editions gives added weight to Harmy’s attitude.

Other Hollywood directors have returned to their films and made changes, some of which have been substantive. Ridley Scott’s director cut of Blade Runner significantly alters the story (and infers that the lead character may be an android). Steven Spielberg returned to his film E.T. and used computers to substitute walkie-talkies for weapons in the hands of FBI officers in a move to make a children’s film even more child-friendly and non-violent. Lucas is more of a troubling figure to fans than these other directors at least partially because of the apparent contradictions in how he views films and their relation to the cultural/historical record. In the 1980s several filmmakers spoke on the floor of the United States Congress in opposition to colorization, a technology that used computers to alter black and white films and television shows by making them color. Lucas acted in defense of filmmakers who wanted their black and white productions to stay black and white and said the following to the congresspersons assembled: “in the future… it will become even easier for old negatives to become lost and be ‘replaced’ by new, altered negatives. This would be a great loss to our society. Our cultural history must not be allowed to be rewritten.” That a filmmaker would express both a sense of propriety over their works and a sense of the historical importance of their preservation is unsurprising. What is surprising is that, years later, Lucas refused to donate a print of the 1977 theatrical version of Star Wars when asked by the National Film Registry so that it may be included in their growing roster of culturally significant films. Not only did Lucas refuse to donate a fresh print of that version of the film, Lucasfilm refused to allow the Library of Congress, which holds a print of the film from 1977, to screen the print. (It is unclear if Disney, which now owns the Star Wars franchise, will have similar restrictions.) Lucas has gone on the record to say about the original version of Star Wars, “to me, it doesn’t really exist any more.” This attitude is what spawned the OriginalTrilogy.com website and community. The website featured a petition, to be sent to Lucasfilm, asking that high-quality copies of the unaltered trilogy be made available to the public. Lucas’ response, when asked about releasing the original cuts of the films: “The special edition, that’s the one I wanted out there. The other movie… it doesn’t really exist anymore. It’s like this is the movie I wanted it to be, and I’m sorry you saw half a completed film and fell in love with it.”

One of the tensions created by Lucas with the fans is the continual versioning of his films. With every subsequent release there are new bits added to or edited from the films. The Despecialized effort exploits this constant re-release by using bits and pieces of various editions to conform into one, definitive, edition. Nonetheless, it is true that multiple versions of a work of art mean that every new iteration complicates the history of the work. It is unclear if Disney will act like Lucas by continually ‘upgrading’ the Star Wars films. In April, 2015 Disney released the Star Wars films for iTunes and other digital download services. While the downloads include bonuses like deleted scenes and documentaries, it does not appear that the films themselves have been changed.

BOOTLEGS AND AUTHENTICITY

The work of Harmy and the Despecialized contributors hinges on the concept of authenticity. From the above discussion it is clear that Lucas and Harmy differ in their views on the authenticity of the Special Editions of the Star Wars trilogy. To Lucas, the film he released (or was ‘ripped from his hands’) in 1977 is not an authentic representation of his vision. It is, in fact, dead to him now that he’s created the Special Editions. To Harmy, Despecialized is an attempt to authentically represent, in a modern, home video context, the experience of viewing the original release. Authenticity is, of course, a broad, malleable concept. The nostalgia component of Despecialized trades on a kind of historical authenticity. While Despecialized clearly conflicts with the original work’s authorial intent (if we define Lucas as the ‘author’ of the Star Wars films – this is, of course, debatable owing to the collaborative nature of film production), it certainly is an attempt to recapture ‘a moment or circumstance now lost.’

This is where Despecialized diverges from most other fan edits. For example, the Phantom Edit is an attempt to map the ‘spirit’ of the original film series (as envisaged by one fan) onto the prequel films by removing sections and characters. Despecialized is not an attempt at manipulating the narrative to create something new, for the most part. It concerns itself mostly with the technical presentation (in terms of sound and image quality) and the ultimate form of the piece. This form itself part of the authenticity, even though it is NOT being presented on film which would, of course, be the most authentic representation of the original theatrically-released artifact.

Despecialized is not the only bootlegged Star Wars video that trades on its technical characteristics to achieve a feeling of authenticity. This kind of authenticity owes to the ‘look and feel’ of an artifact, in this case a copy of a television broadcast. The feeling of authenticity of copies of the “Holiday Special” owe to the inclusion of television commercials, tracking errors (likely induced by the comparatively crude off-air capture devices of the late 1970s), smearing colors, tinny sound and so on. While Harmy goes to great pains (detailed on his YouTube page) to get a ‘filmic’ quality to Despecialized in order to evoke the theatrical experience, the “Holiday Special” bootlegs revel in their televisual quality.

Most bootlegs of the “Holiday Special” leave in the commercials. In much of our regular television viewing, commercials are a nuisance. The “Holiday Special” bootlegs seem to revel in them. After all, it would be an easy thing to edit them out. Each bootleg – the “Holiday Special” and Despecialized – is at least partially an attempt to replicate something that cannot entirely be replicated: an experience of ‘what it was like then.’ And since Lucas has gone to such great pains to shield both the “Holiday Special” and film prints of the 1977 Star Wars from public exhibition, both bootlegs represent attempts to wrest a creator’s ownership of his creations from him in the name of access.

AURA AND DISPOSITIF

Lucas’ intentions for the Star Wars films have long troubled the films’ fans. From the inclusion of CGI in the Special Editions to the preponderance of CGI in the Star Wars prequel films, Lucas has continually alienated sections of his fan base. Despecialized represents a kind of organized resistance to Lucas’ continual refashioning of his stories by attempting to freeze moments in time by preserving the theatrical releases of the original trilogy. Many of the Despecialized contributors (but not, surprisingly, Harmy himself) were first exposed to Star Wars in its 1977 theatrical iteration and so the aura of that version is what they are trying to recapture in their collaborative effort. One method employed by Despecialized for recapturing the aura of the original trilogy is to undo the CGI that Lucas added in the 1990s. This removal of computer imagery reflects – knowingly or not – a larger, ongoing debate among film fans regarding the authenticity of this modern form of special effects technology. The special effects of the first Star Wars trilogy were, prior to the Special Editions, optical effects. That means that, for most effects scenes, something (a spaceship, a monster, a futuristic weapon) had to exist in real space to be filmed. In the world of CGI, there are sometimes referents that exist in space for animators to use, but the ultimate products are created in the digital realm and composited into the real. Nowhere is this reverence for ‘cheesy’ special effects – and the feelings of authenticity and presence that they can engender – more on display than in Star Wars Despecialized. With this fan edit one kind of verisimilitude (real-and-diegetic – it was there in front of a camera on the day of filming and appears to inhabit filmic space) is prioritized over a different kind (digital-and-diegetic – it may not have been there on the day of filming but it looks very real to my eyes and so appears to better inhabit the filmic space than a practical effect).

No amount of attention to detail in the digital audiovisual object created by the Despecialized community will ever capture the dispositif (a kind of aura) of the original release. We will, at best, be left with a high quality representation of what a portion of the theatrical experience would have been like, scrubbed free of the smell of the theater popcorn, the brightness or dimness of the projection, the comparative thinness of the theatrical sound projection (compared to Despecialized’s robust 5.1 audio mix) and, perhaps most importantly, the thrill of seeing the film for the first time before it became a household name. But, of course, no home video iteration of a theatrically-released film can ever capture those elements of a dispositif.

The promotion of the Despecialized films clearly plays off of a different kind of aura – the look and feel of the branding of the official releases of the Star Wars films on home video. His YouTube making-of video uses bits of John Williams’ scores from the original trilogy and the downloadable ‘packaging’ for Despecialized appears to be polished and similar in tone to official releases. This branding of a fan edit (itself a kind of attempt at authenticity – you want to make sure the ‘consumer’ gets the ‘real’ product) is common among fan edits.. This packaging and branding of Despecialized emulates a different kind of dispositif – one of traditional home video distribution and collection.

CONCLUSION: A NEW HOPE FOR STAR WARS FANS

In recent years audiences have seen ‘reboots’ of several Hollywood science fiction franchises: The Terminator, Mad Max, Jurassic Park and even Star Wars. Because the directors of several of these films are, like J.J. Abrams, self-professed fans of the worlds in which they are playing, it is hard to see these remakes and sequels as anything other than well-funded and ‘officially’ distributed fan edits themselves. Some of these films, like 2015’s Terminator: Genisys and 2009’s Star Trek integrate actors, situations and even footage from their earlier incarnations to create time-bending narratives that, in some cases, rework the established continuity of those series. As Hollywood becomes more risk-averse than ever, it has mined 1970s and 1980s nostalgia for newly-viable properties and is, like some fan editors, reworking existing footage and characters to infuse these new creations with the aura of authenticity.

The sale of Lucasfilm to Disney means that George Lucas no longer has creative control over the Star Wars realm. It is possible that Disney will concede to fan pressure and release high-quality iterations of the original, unaltered trilogy. Would this nullify the work of Harmy and his compatriots? In one sense it would: consumers could legally purchase copies of these films in whatever formats Disney releases them. However, in another sense, the Despecialized efforts – and the larger fan edit culture in which they have been incubated – represent a window into a much larger issue of just who owns cultural products like Star Wars. Disney’s claim to ownership of the franchise is, like Lucas’ claim before it, legally binding in the eyes of American copyright law. Fan edits like Despecialized, however, are assertions that fans, consumers and viewers of cultural products have a claim to ownership as well. The work of many fan editors seems to make the claim that, even if these fans do not own a film, they may have some ownership of the spirit of that film. Harmy’s claim is that the preservation of and access to the original versions of the Star Wars trilogy cannot be left to their creator and/or legal guardian because he cannot be trusted to do right by fans and by the historical record. With Despecialized Harmy and his contributors are making the claim – sometimes explicitly and sometimes implicitly – that films belong to posterity.